“Everybody just automatically assumes that the internet is just going to work wherever they are. If I’m on an aeroplane, I’m not going to use an entirely different method of accessing a network.”

This is the central point of Valve’s announcements last week. They are the solution to a problem Gabe Newell proposed at LinuxCon two weeks ago.

“We think that should be true more broadly. You don’t think of touch input, or tablets, or game controllers, or living rooms – ways for users to interact, ways of acquiring digital assets, or ways for developers to program or distribute to those targets.”

Newell and Valve have been looking at boundaries. Now, they’re getting into the business of breaking them down.

“Those closed platforms are not going to be able to provide that grand unification between mobile, the living room, and the desktop.”

“As soon as you sit on a couch, you’ve completely lost connection to all your other computing platforms. You’re meant to just buy all your games all over again. We think that through thinking about design, about thinking through abstraction for both users and developers, you could build something that has the best 10 foot living room experience.”

His and Valve’s point: games are games, software is software, assets are assets, and the walled gardens that Microsoft, Sony, Nintendo, Apple and Google have placed around their content ecosystems are a problem.

So how do we get from PC gaming as of now, to the ubiquitous platform agnostic game delivery service Gabe and Valve are aiming for?

Valve’s first step is obviously Steam OS: a Linux based operating system (widely believed to be using Ubuntu as its base) that uses Steam’s living room focused Big Picture Mode as a front-end.

The second: a wave of Valve approved PC hardware that can play PC games in silent conditions, and not look terribly out of place under a television.

And finally, a new type of controller.

And it’s the third piece of the puzzle I think is the most interesting.

Valve’s Steam Controller announcement begins with this: “We set out with a singular goal: bring the Steam experience, in its entirety, into the living-room….We realized early on that our goals required a new kind of input technology — one that could bridge the gap from the desk to the living room without compromises.”

For an example of those compromises, look to Irvine, California. When Blizzard ported Diablo III to the XBox 360 and PS3 it required a major redesign: characters movement and abilities were altered, monster AI was adjusted to make it more friendly to controllers, loot drop frequency was reduced, even the interface was completely redesigned. Diablo III’s PC version just didn’t work when when transferred to a joypad.

Valve’s problem is even harder: if you throw the mouse and keyboard out of the window, how do you play Dota 2? How do you play Eve Online? How do you play Civ, ArmA, Train Simulator, Company of Heroes, or Total War, on a television that is ten feet away? It’s not just that the joypad isn’t the right device for controlling a nation’s finances, or organising a last minute defense of a tower. It’s that the very interfaces themselves may not even be visible at distance.

Hence: two innovations – thumbsticks are replaced with touchpads that can poke and prod back at you, and the entire centre of the controller is a touchscreen that reacts to a click – where developers will eventually be able to summon menus and options, similar to a right mouse button.

Will it work?

Those that have played games with the controller suggest that it is a fine solution for playing games designed for a joypad. That almost feels like an irrelevance. If I want to play Spelunky on the Steambox, I can always just plug in a wireless 360 controller.

“Will it work?” isn’t that interesting a question. I want to know, “how will it work for PC games?”

My gut says that out of the box, not spectacularly. It’s going to take some work and lateral thinking for developers and their communities to create decent bindings for the games they want to play. Developers will need to access and understand the controller APIs if they are going to make best use of the touchscreen and pads.

The PS4 has a similar multi-touch pad on its joypad, and I found it a bit awful. Whether that’s down to developers struggling to calibrate their software to its functions, I don’t know – but playing next-gen games at GamesCom, I couldn’t find a single game that got a decent set of options out of the pad. Where it was used to zoom in and out of map screens it was glitchy and imprecise.

I wonder, as well, if the touchscreen might be a missed opportunity. Stretch it out over a few more inches, and rather than just displaying interface elements, the entire display could be mirrored between your fingers. Quietly, the controller could be used as the equivalent of Nvidia’s Shield – streaming PC games to your hands when you’re at home, but away from a bigger screen. Maybe there’s room for an XL version of the Steam Controller, that can access your Steam library from your bed.

So, to the hardware.

The Steam Machines announcement was long expected: earlier this year, Gabe explained that Valve would be releasing three machines of their own. A great PC, a good PC, and a super-cheap streaming box that could be sold for around $99, or even for free.

Home-streaming is alluded to on the Steam Machines page, as something Steam Machines are capable of: decoding streams of Windows games from your home PC to the Linux box. But there’s very little sense that a small gadget for streaming games is still on Valve’s immediate agenda.

There are a couple of reasons why they might want to slow down on the streaming tech: the first is that by putting out the full Linux boxes first, they can test how streaming works in real-world conditions using early adopters as guinea pigs.

The reality is that home-streaming isn’t quite ready: I think if it launched tomorrow, we’d all be disappointed with the results. Miracast (an industry standards based solution for streaming from tablet to screen) can be laggy, while Nvidia’s Shield introduces some latency that makes twitch games difficult to control.

Feedback and analysis from early adopters of the more powerful boxes could be used to directly improve a mass-market widget, similar to an Apple TV, or Ouya. It would allow Valve to figure out what optimisations they can make in the Steam client and the device itself, ahead of a launch later in the year.

Second: I think that a streaming box dilutes the impact of what Valve are attempting with Steam OS: lobbing an open source flavoured hand-grenade at Microsoft.

One of the criticisms I’ve read of Steam Machines are that they’re going to be expensive. I don’t agree.

For one, I don’t think they need to be particularly powerful. Valve have repeatedly explained that after optimisations, they’re seeing superlative performance from their Linux native development. The hardware is targeting a very specific type of display: a 1080p television. There’s no need to create headroom for multiple monitor setups, or crazy high resolutions. The new consoles aren’t exactly wielding terrifying levels of hardware in their boxes. And the price can be reduced further by not paying a tithe to Microsoft for the privilege of running Windows 8.

I don’t think they’re going to be cheap either. Valve can’t really justify selling them at a loss. Consoles can be sold at a loss as long as the buyer goes on to purchase more games. Closed systems are good for this. If they’re as open to hacking and modifying as Valve promise, there’s no way to stop an IT manager buying several and kitting out an office with cheap as chips workstations.

I question whether Valve will actually create their own hardware. I think it’s probably better for PC gaming and gamers if they leave the manufacturing to separate companies, but provide licensing and branding to the developers. Think of it as the equivalent to Android in mobile hardware and software. But that model has to leave some profit for the manufacturers.

I think that a standard issue Steambox could end up costing around the same price as an Xbox One: say around £400+. Then you’re on a sliding scale: if you want to upgrade the CPU and GPU, add an SSD, and go for 16Gb RAM, then go nuts. If you can afford it.

But! There is one way that Valve could help mitigate the cost of the hardware beyond a straight subsidy: by providing Steam credit to everyone who purchases the device. £100’s worth of Steam vouchers can stretch a very, very long way.

I don’t see the Steam Universe project as competing directly with the next-generation consoles. At least, not to begin with. I think there’s very little chance a console gamer is going to switch to PC following Valve’s announcements. There’s no way Valve can marshall the kinds of budget and manpower Microsoft and Sony can afford to spend on exclusive software development, marketing and developer support.

Where I think it can compete is in software sales. Valve are launching a living room device that can already play 3000+ games, 200+ of which will be native from the moment it launches. The commitment Valve have quietly made is that every game bought on Steam between now and the end of time will be playable on every Steam device you own. That is a powerful promise.

If I was choosing to buy a cross-platform game, I would inevitably choose to buy that game on Steam over and above the next-gen consoles. It will be cheaper, will look as good if not better, will be playable on many devices including my home PC and my living room, can be shared with my family, and savegames and progress will migrate to all the machines I play on.

That’s a hell of a promise.

Do players want this?

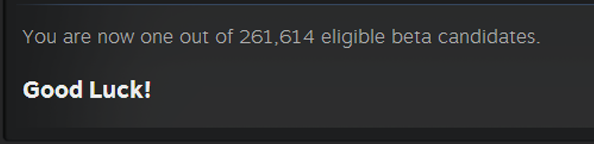

For a measure, we can take a look at the signups for the hardware beta. Valve are offering 300 PC gamers the chance to test a Steambox – to receive a PC and the new controller for free. To be eligible, all you needed to do was open up Steam and play a game in Big Picture mode. At time of publishing, 261,000 players have signed up.

The announcements received wall to wall media coverage, reached the top of Reddit, were featured in stories on Valve’s homepage and were advertised on Valve’s game exit popups. Given just how many gamers will have seen the coverage, I’m amazed that only 260,000 people signed up. That doesn’t feel like a very big number in context. For comparison, the promise of an Elder Scrolls Online beta led to three million signups.

Here’s my worry: for all of its promise, there’s a long way to go to explaining why the Steambox matters, and why gamers will benefit from what Valve are attempting.

—

I honestly don’t know if this new direction Steam is taking will work. I have no idea how Valve will measure its success, where in sales of Steam Machines or take up of the Steam OS, or even games converted to use the Steam Controller. I wouldn’t even like to put a hand in the air and try and guess the sales of Steam Machines or Controllers.

I think, initially, they will be slow, at least compared to traditional game consoles, but that is probably fine. I believe that Valve see this as the beginning of a very, very long-term project. The first waves of announcements are little more than experiments to gauge what the community really wants. I believe that, rather than looking at what they are doing as a traditional hardware launch, a better comparison is the open, public development of Dota 2 – a new feature, and new reason to get involved added every week.

I can’t imagine a more exciting project in gaming. I can’t wait to see it come alive.