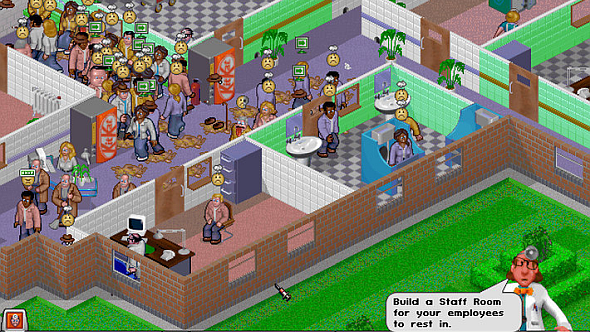

Treating cancer is a bit of a downer in a family-friendly management sim. That’s why Two Point Hospital invents a bunch of pun-based fictional diseases and presents them in a cartoonish setting. Like the afflictions in 1997’s Theme Hospital, they are designed to raise a smile: gray anatomy, verbal diarrhoea, and who could forget bloaty head?

But if you think about it, these diseases, and certainly their treatments, are actually pretty horrific. What would Two Point Hospital look like if it weren’t a cartoon?

To stay in your cosy world of videogames, check out our Two Point Hospital gameplay preview.

I push through the surgery doors and blow out my cheeks, tossing bloodstained gloves into the bin. Eight hours. Eight hours of painstaking unwrapping, slow and deliberate so as not to rip any skin away with the bandage, like peeling an endless sticker from the cover of a new book. Damn if mummification isn’t a pain to treat.

But I’m finally done and the patient is in recovery – with urgent advice to never again set foot in the British Museum – thanks to these miracle-working fingers of mine. Time to clock off. Maybe I’ll head to the staff room first, sneak in a nap on the comfy sofa…

Oh no. That’s my name being called over the tannoy. I’m urgently needed, and no-one else will do.

“Dammit,” I mutter. Curse these miraculous fingers.

I crack my knuckles and jog to reception just as a team of paramedics push a gurney through the front doors. Its occupant lies completely still beneath a blanket that covers their entire body, though there’s an ominous glow where their head would be. The gurney gathers a crowd of grim-faced nurses and doctors like a turd rolled through glitter.

“Presentation?” I ask of the paramedics, in a clear, commanding tone.

“Lightheadedness,” the lead medic whispers, her voice quivering.

“My god.”

An intern doctor laughs, incredulous at my solemnity. “Well, that doesn’t sound so bad. Surely we advise a healthy meal and a nice lie-down?”

The more experienced staff exchange looks of concern. I slap the intern around his fresh, naive face, because it feels like the dramatic thing to do.

“Educate yourself or get the hell out of my hospital, rookie!”

“Bu – but…”

“Where’d you train? Haven’t you heard? Lightheadedness is the new bloaty head!”

In unison, those doctors senior enough to remember the bloaty head epidemic of ‘97 look at the intern like he’s asked to urinate in their cornflakes. That was a dark time. Our only treatment was to re-inflate patients’ heads after puncturing them – I can still remember the stink of the pus. The intern stares at the linoleum floor, ashen-faced, holding back tears. Good. It’s tough love, but he’s got to learn: lightheadedness is not to be taken lightly.

After five minutes of pushing the gurney through double sets of swing doors – someone has laid this hospital out really badly – we reach the operating theatre.

“Bayonet or screw?” I bark.

The lead medic is shamefaced. “We… we didn’t have the guts to check, doctor.”

“Dammit,” I mutter again. Pretty sure I nailed the gravelly voice. With a flourish I remove the blanket, revealing a bulbous glass head and the brightly burning filament inside – it crackles with anxiety. I check the poor fella’s neck.

“Screw,” I declare. A nurse’s hand shoots to her mouth. The intern turns to vomit on the floor. I slap him again and call for the pincers. “No time to screwaround,” I say, deftly deploying a bit of humour to raise morale.

But my quip conceals a point of deadly seriousness – judging by the rusty hue of its light, the filament is about ready to pop. And when that happens, well. You don’t want to know.

“Restrain the patient,” I command, and the small army of attendants secure a limb each. The pincers are the size of bolt cutters – squinting against the searing light of the bulb, I close the jaws around the patient’s neck and squeeze my arms around the handles. I slap the intern one more time for luck – we all have our superstitions – and drop my weight, pulling the pincers down.

There is resistance at first, but the patient can clearly feel the pressure – he writhes in mute agony, and the staff struggle to contain his thrashing. My feet are off the floor, the full weight of my muscular 216 lbs applied to the pincers, and then something gives with a thick crunchfrom deep within the patient’s neck. The sound is like someone crushing a crisp packet inside a bowl of custard. This, unfortunately, is the treatment for lightheadedness: unscrewing the bulb from the patient’s spine. Naturally, general anaesthesia would be called for, but light bulbs can’t inhale gas. Duh.

After a quarter-turn the pincers are near the floor. I unclench the jaws, reset them, and repeat the procedure. Sweat beads on my brow, and on those of the attendants as they hold the patient down. But for their effortful grunting and the susurration of sheets on the gurney, it’s disturbingly quiet. I’d almost prefer it if sufferers of lightheadedness could scream.

There is more crunching, more grinding, until finally the filament flickers and goes dark, and it’s as if the entire room exhales.

“Well done, everyone,” I say. “We can do the rest by hand now.”

Perhaps eager to compensate for his earlier insouciance, the intern hurries over to finish the job. He reaches out for the bulb itself…

“Not like that, you fool!”

The intern places both hands on the searingly hot glass, and immediately withdraws them with a scream that’s all the more shocking for the silence of the patient just a moment ago. He leaves two black palm prints on the bulb, trailing oily smoke and the scent of burned plastic – the remains of his surgical gloves, flash-melted. I think of my mummification patient earlier today, of how careful we were not to tear the skin away with the bandages.

His scream still ringing round the tiled walls, the intern is huddled in the corner of the operating theatre, staring at his shaking hands in horror. I can’t tell where plastic ends and flesh begins. There is blood and the smell of cooked meat.

Staff rush to help him to his feet, and to offer words of consolation, but he can’t look away from his hands. For once today, he is thinking what I am thinking.

Those hands will work no miracles.