Prey’s Talos 1, an art-deco space station hanging in the black like a gleaming obelisk, is littered with baseball gloves. No matter where you go, they’re scattered around: floating through the zero-G chambers, plonked on desks, and shoved in the pockets of Talos 1’s murdered inhabitants.

If you like your galactic adventures minus the threat of floating props, check out our list of the best space games.

Developers Arkane admit they got carried away with catching mitts, a prop devised by lead environment artist Eric Beyhl, who just happens to be a huge baseball fan. The team in charge of set-dressing loved them and they ended up absolutely everywhere. In fact, they’re so prolific that you might expect to stumble across a giant baseball stadium buried somewhere deep within the space station. Still, Arkane made it work.

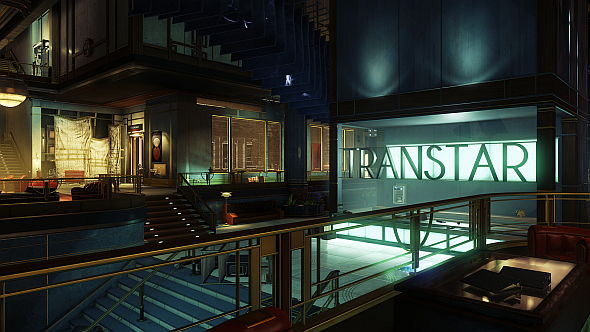

“We started trying to figure out what sort of story we were telling with this,” lead designer Ricardo Bare tells me. “It [had something to do with game designer] Steve Powers, the guy who was responsible for taking care of the character database. One of the characters is on the sales team. In the lobby, there’s a sales office, and those guys take briefcases full of neuromods, load them onto a shuttle, and fly down to Earth to sell them to rich clientele. One of these guys is an ex-professional baseball player.

“You’ve probably heard the story of ‘What did the ex-professional football player do? Well, he became a car salesman’. It’s that sort of deal. This guy washed out of the major leagues and got a job as a salesman for TranStar. But when he joined the company, he had boxes and boxes of signed baseball gloves, so he just handed them out as gifts to all the employees on the space station. There’s all these journal entries where he’s sad because people don’t seem that excited about his baseball gloves. It kind of shows that when you’re creating art, you can unintentionally tell funny stories that add a lot of humour and depth to the game.”

Baseball gloves in Talos 1 are emblematic of how videogames are made – how things change over the course of development, and how a tiny detail can alter another aspect of the finished product. This is a prop that was originally just supposed to humanise the residents of Talos 1 with a slice of home, but it ended up adding meat to the story, too. Prey wasn’t always going to be set on a space station, but Arkane had one rule during the concept phase: the game must be a self-contained environment, not a series of missions. Arkane wanted players to feel trapped. They wanted players to become intimate with a place that slowly evolves as they play.

“We had some ideas inspired by other movies or books that we’d read, things like ‘What if it was a fake city?’,” Bare recalls. “The other thing we wanted to do is something where you think ‘this is the truth’, but ‘Surprise! This is actually the truth’. Lots of little twists and turns like that. Our idea was ‘What if it’s like a fake city that’s almost an ant farm for humans, and it’s being curated by some aliens?’ We had another idea that was like Lost, set on an island that’s super mysterious, and you’re not sure why you’re there or what’s going on. It wasn’t even a long [decision process]. Very quickly, we decided ‘Hey, let’s have the structure of Arx Fatalis, but we’re all huge fans of System Shock, so let’s do something like that.’”

The end result takes the structure of Arkane’s Arx Fatalis and plonks it in the claustrophobic space setting of System Shock, Looking Glass’s sci-fi RPG. Publishers Bethesda were sitting on the Prey brand, following the cancellation of Prey 2, and so decided that Arkane should use the name for their game.

Despite Prey having nothing to do with the Human Head Studios’ original, some small story details were switched up. For example, your brother, Alex Yu, was originally going to be a friend from college. January, an AI that was to be based on your own personality, was called Danielle, and had a much larger role. In the following prototype, January wasn’t even based on Yu’s personality – it was just an AI with unknown intentions. Then the team decided to make protagonist Morgan Yu mute, so the decision was made to make these machines a cipher for his personality, transferring his voice onto the AI. It may sound like an existential nightmare, but it turned out to be the perfect compromise.

Arkane wanted to avoid having moments where Yu was saying things that the player wouldn’t connect with, so this solution allowed them to have the best of both worlds. There’s plenty of character elsewhere aboard Talos 1, after all. To give the station a truly lived-in feel, for example, Arkane created NPC residents, both those who survived the outbreak of the Typhon alien forms, and those who didn’t. Some of them are now phantoms, roaming the station as shadows. Recently deceased or otherwise, every NPC is important – the player can track each and every one of them via a security terminal to discover their fate. It’s an expansive cast – Arkane created around 250 of them.

“We already had this system in development where you were going to be able to use security computers to find certain quest-related people,” Bare remembers. “I think it was our lead level designer Rich Wilson who suggested: ‘Why don’t we just apply that globally? Instead of having dead generic corpses.’ We already had this system where you could log into a computer and find doctor so-and-so, so why didn’t we just list everyone? And instead of being super explicit and scripted, the player can ‘opt-in’ to using that system at any time.

“Anytime the game asks them to find somebody or when they want to find somebody. That system just populated the names onto the corpses, basically. One of our local designers, Steve Powers, who’s really good with narrative stuff, curated that list. He came up with all the names of every person, and they all have varying levels of detail to them depending on how much time the player was going to spend on that person.”

To make tracking these people down rewarding, Arkane used clever environmental storytelling in combination with audio logs. In Prey, though, props are even more important than usual.

“From an art perspective, there’s already a kind of ‘studio’ culture with it, because one of the things the team in Lyon does really well is environmental storytelling,” art producer Jessie Boyer explains. “They try to imagine what the people would be doing on their daily routes. For us, we already had intentions of doing that, so it wasn’t a stretch to take that to the next level. When we were trying to imagine the people, it actually helped to have that roster system. I could just go to Steve, Rich, or Ricardo and be like ‘Hey, what kind of hobbies does this person have?’ and we could really tell a story with the props we had available to us.”

The team had lots of meetings about this, discussing how many people would feasibly work on a space station the size of Talos 1. They tackled each department, from engineering to the science labs, figuring out how many people worked there, before settling on the total number NPCs. From there, they gave each character a job description. Later in the game you find out that station volunteers are being murdered by Mimics in order to create ability-giving neuromods – Arkane even took that into consideration when placing neuromods in the world, figuring out how many made sense and even noting how much money TranStar, the corporation behind it all, had made. The development team tracked this information through infographics, some of which can be found hidden around Talos 1.

This attention to detail in making the inhabitants of the station feel human, and the station itself feel lived in, is unparalleled. A standout moment sees you stumble across the sleeping pods of some of the station’s residents. In each, you find little details about their lives: photos from back home, notes, children’s drawings, and more – for added authenticity, those drawings were made by the children of Arkane employees. These small details are used in combination with bigger stories to make the residents of Talos 1 – even the dead ones – come alive.

Among many memorable discoveries, there’s a love story that develops between two women, which you get to follow to its heartbreaking conclusion. One of the women in the story is Danielle, the prototype AI, repurposed for a new story. And you see a Dungeons & Dragons-style pen and paper RPG, that was being played by the Talos 1 staff, unfold as you travel between the different departments.

“The D&D game was fun, because the Crew Facilities was one of my favourite levels. Rich Wilson and Albert Meranda worked on it,” Bare tells me. “That level’s great because it’s one of the most humanising spaces in the game. A lot of people pitched in with ways to ground everyone’s lives with real details. What do they eat? What do they do for fun? They’re not always in a laboratory pouring fluids into beakers or dissecting aliens. They have to blow off some steam and hang out. They develop relationships.

“We wanted the crew quarters to represent that human, unscripted side of their lives. One of the ideas was ‘What if the five of them played tabletop games in the rec center?’ We had audio logs of their gaming sessions, and later Rich tried to tie that into the quest to find all of Danielle’s voice samples, so she became somebody who was part of the game. If you’re trying to find Danielle’s voice samples, you stumble upon the gaming session that she’s a part of, and incidentally you learn about all these other characters. It’s a bit of an allusion to Arx Fatalis, because the roleplaying game they’re playing is called Fatal Fortress, which is just English for ‘Arx Fatalis’.”

Storytelling is all very well, but Arkane’s mastery is further demonstrated by the fact that the placement of these storytelling tools also serves a gameplay purpose in Prey. Mimics can morph into these items and spring a trap, as can the player if they decide to use neuromods. It’s a recipe for paranoia.

“Later in the game, artists would deliberately put two or three of something next to each other just to smoke the player out,” Bare laughs.

“There’s one character that has dementia,” adds Boyer, “so at one point we made sure to place a lot of cups and a lot of notepads in a room, like he was constantly forgetting where he was putting his stuff. Little things like that could unintentionally build some tension in this dark corner that’s full of cups [laughs].”

To make sure there were at least somerules players could acknowledge, Arkane decided that Mimics could only become props that were no smaller than a coffee cup, and no bigger than an office chair. This made environments more readable, ensuring you wouldn’t crap your pants walking past a refrigerator.

Still, that paranoia remains. It’s a masterful marriage between game mechanics and storytelling. What better way is there to make a player take notice of the work that’s gone into environmental storytelling than to make them scared that the props might murder them? In doing so, Arkane ensures players are scanning every room carefully, taking note of all the small details, and praying that every baseball glove they find won’t suddenly turn sentient and try to eat their face like a rubbery facehugger.

This feature was originally published on August 14, 2017. Read more about Prey.