April 12, 2024: With the launch of the Fallout TV show, we’re taking a trip down memory lane to reshare some of our classic Fallout coverage. This post was originally published in October of 2017.

Tim Cain was at PAX when he first saw Vault Boy as a living, breathing entity – it was a cosplayer of 16 or 17 years old, hair gelled to replicate that distinctive swirl. ‘This is weird’, he thought. Feargus Urquhart remembers walking into Target and seeing that same gelled haircut and toothy smile, not on a fan this time, but emblazoned across half a meter of cotton. ‘How is it that a game that we all worked on somehow created something iconic?’, he wondered. ‘How did it show up on a t-shirt in a department store?’

In the years since, Bethesda has taken Fallout into first-person, online, and the pop culture mainstream. Vault Boy has become as recognizable as Mickey Mouse. The series’ sardonic, faux-’50s imagery now feels indelible, as if it has always been here. But it hasn’t.

It took the nascent Black Isle Studios to nurse the Fallout universe into being, as an unlikely, half-forgotten project in the wings of Interplay, where Cain and Urquhart were both working in the ‘90s. The pair helped create one of the all-time great RPGs in the process.

“The one thing I would say about Interplay in those days, and this isn’t trying to pull the veil back or anything like that – there was just shit going on,” Urquhart tells us. “It was barely controlled chaos. I’m not saying that Brian [Fargo] didn’t have some plan, but there was just… stuff.”

One day, Fargo sent out a company-wide email to canvass opinion. He wanted Interplay to work on a licensed game, and had three tabletop properties in mind. One was Vampire: The Masquerade. Another was Earthdawn, a fantasy game set in the same universe as Shadowrun. And the third was GURPS, designed by Steve Jackson.

The team picked the latter, overwhelmingly, because that was what they played in their own sessions. But GURPS wasn’t a setting – it was a Generic Universal RolePlaying System. And so Interplay’s team had to come up with a world of their own.

“I would send out an email saying, ‘I’m in Conference Room Two with a pizza’,” Cain says. “And if people wanted to come, on their own time, they could do it. Chris [Taylor, lead designer], Leonard [Boyarksy, art director], and Jason [Anderson, lead artist] showed up.”

Interplay at the time was almost like a high school, as map layout designer Scott Everts remembers it: incredibly noisy and divided into cliques. Cain was building a clique of his own.

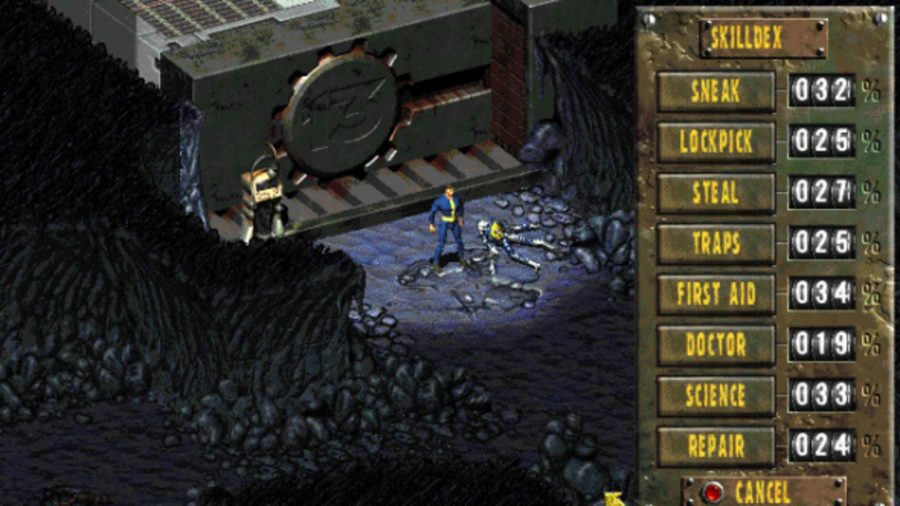

Traditional fantasy was the first idea to be dismissed. The team actually considered making Fallout first-person, a decade early – but decided the sprites of the period didn’t offer the level of detail they wanted. Concepts were floated for time travel, and for a generation ship story – but one after the other, they were all pushed aside and the post-apocalypse was left.

“One thing I didn’t like was games where the character you’re playing should know stuff that you, the player, don’t,” Cain says. “And I think the vault helped us capture that, because both you the player and you the character had no idea what the world was like. The doors opened and you were pushed out. And I really liked that, because it meant we didn’t have to do anything fake like, ‘Well you were hit on your head and have amnesia’.”

There was plenty about the Fallout setting that wasn’t as intuitive, however. Players would have to wrap their heads around a far-future Earth and a peculiar retro aesthetic, even before the bombs started dropping. The question of how Fallout ever survived pitching is answered with a Cain quip: “What do you mean, pitch?”

For a short while, Interplay had planned to make several games in the GURPS system. But soon afterwards it won the D&D license, a far bigger property that would go on to spawn Baldur’s Gate and Icewind Dale. As a consequence, Cain’s team were left largely to their own devices.

As for budget – Fallout’s was small enough to pass under the radar. Although Interplay is best remembered for the RPGs of Black Isle and oddball action games like Shiny’s Earthworm Jim, the studio had mainstream ambitions not so different to those of the bigger publishers today. During Fallout’s development Interplay was primarily interested in sports, and an online game division called Engage.

“It was almost like a smokescreen,” Urquhart explains. “So much money was being pumped into these things that you could go play with your toys and no-one would know.”

Which is exactly what the Fallout team did, pulling out every idea they’d ever intended for a videogame.

“Being just so happy and fired up that we were making this thing basically from scratch and doing virtually whatever we wanted, we had this weird arrogance about the whole thing,” Boyarsky recalls. “‘People are gonna love it, and if they don’t love it they don’t get it.’

“Part of it was a punk rock ethos of, every time we came up with an idea and thought, ‘Wow, no-one would ever do that’, we always wanted to push it further. We chased that stuff and got all excited, like we were doing things we weren’t supposed to be doing.”

The team laugh at the idea that Fallout might have carried some kind of message (“Violence solves problems,” Cain suggests). To these kids of the ‘80s, nuclear holocaust felt like immediate and obvious thematic material. The game’s development was guided by a mantra, however.

“It was the consequence of action,” Cain puts it. “Do what you want, so long as you can accept the consequences.”

Fallout lets you shoot up all you want. But if you get addicted, that will become a problem for you, one you’ll have to cope with. The team were keen not to force their own views onto players, and decided the best way to avoid that was with an overriding moral greyness.

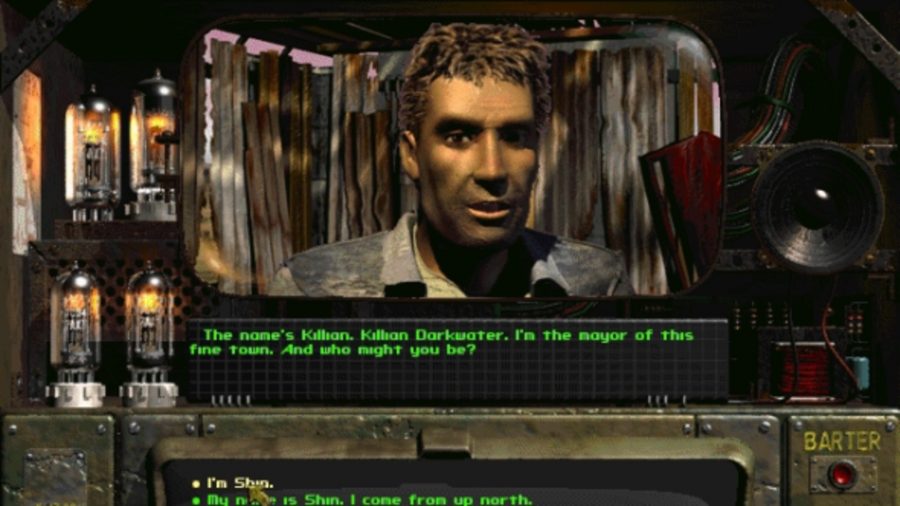

The Brotherhood of Steel – in Fallout 3, a somewhat heroic group policing the wasteland – was here in the first game simply as preservationists or, more uncharitably, hoarders. Even The Master, the closest thing Fallout had to a villain, was driven by a well-intentioned desire to bring unity to the wasteland. His name, pre-mutation, was ‘Richard Grey’.

“Everyone needed to have flaws and positive points,” Taylor says. “That way the player could have better, stronger interactions whichever way they went.”

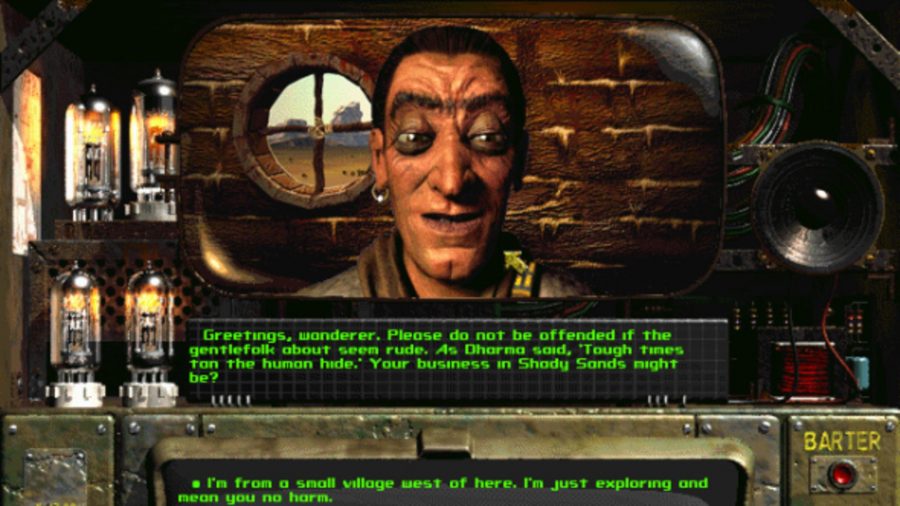

Although the GURPS ruleset eventually fell by the wayside, the Fallout team were determined to replicate the tabletop experience they loved – in which players don’t always do what their Game Master would like. They filled their maps with multiple quest solutions and stuffed the game with thousands of words of alternative dialogue. “The hard part was making sure there was no character that couldn’t finish the game,” Cain says.

Fallout’s dedication to its sandbox is still striking, and only lately matched by the likes of Divinity: Original Sin 2. It was a simulation that enabled unforeseen possibilities.

“I am shocked that people got Dogmeat to live till the end of the game,” Taylor says. “Dogmeat was never supposed to survive. You had to do some really strange things and go way out of your way to do so, but people did.”

During development, a QA tester came to the team with a problem: you could put dynamite on children.

“Where you see a problem…,” Urquhart says. He is joking, of course, yet the ability to plant dynamite – achieved by setting a timer on the explosive and reverse pickpocketing an NPC – became a supported part of the game and the foundation of a quest. This was a new kind of player freedom, matched only by the freedom the team felt themselves.

“We were really, really fortunate,” Boyarsky says. “No-one gets the opportunity we had to go off in a corner with a budget and a team of great, talented people and make whatever we wanted. That kind of freedom just doesn’t exist.

“We were almost 30, so we were old enough to realize what we had going on. A lot of people say, ‘I didn’t realize how good it was until it was over’. Every day when I was making Fallout I was thinking, ‘I can’t believe we’re doing this’. And I even knew in the back of my head that it was never going to be that great again.”

Once Fallout came out, it was no longer the strange project worked on in the shadows with little to no oversight. It was a franchise with established lore that was getting a sequel. It wasn’t long before Boyarsky, Cain, and Anderson left to form their own RPG studio, Troika.

“We knew Fallout 1 was the pinnacle,” Boyarsky says. “We felt like to continue on with it under changed circumstances would possibly leave a bad taste in our mouths. We were so happy and so proud of what we’d done that we didn’t want to go there.”

Fallout is larger than this clique now. Literally, in fact: the vault doors Boyarsky once drew in isometric intricacy are now rendered in imposing 3D in Bethesda’s sequels. And yet Boyarksy, Taylor, and Cain now work under the auspices of Obsidian, a studio that has its own, more recent, history with the Fallout series. Should the opportunity arise again, would they take it?

“I’m not sure, to be very honest,” Taylor says. “I loved working on Fallout. It was the best team of people I ever worked with. I think it’s grown so much bigger than myself that I would feel very hesitant to work on it nowadays. I would love to work on a Fallout property, like a board game, but working on another computer game might be too much.”

Boyarsky shares his reservations: that with the best intentions, these old friends could get started on something and tarnish their experience of Fallout.

“It would be very hard for us to swallow working on a Fallout game where somebody else was telling you what you could and couldn’t do,” he expands. “I would have a really hard time with someone telling me what Fallout was supposed to be. I’m sure that it would never happen because of the fact that I would have that issue.”

Urquhart – now Obsidian’s CEO – is at pains to point out that Bethesda was nothing but a supportive partner throughout the making of Fallout: New Vegas, requesting only a handful of tiny tweaks to Obsidian’s interpretation of its world. “I’ve got to be explicit in saying we are not working on a new Fallout,” he says. “But I absolutely would.”

Cain has mainly built his career by working on original games rather than sequels: Fallout, Arcanum, Wildstar, and Pillars of Eternity. But he would be lying if he said he hadn’t thought about working on another Fallout.

“I’ve had a Fallout game in my head since finishing Fallout 1 that I’ve never told anyone about,” he admits. “But it’s completely designed, start to finish. I know the story, I know the setting, I know the time period, I know what kind of characters are in it. It just sits in the back of my head, and it’s sat there for 20 years. I don’t think I ever will make it, because by now anything I make would not possibly compare to what’s in my head. But it’s up there.”